Saturday, December 31, 2005

The colours of spring

What is he singing about? Love? Realisation? A new journey? Everything. Everything that anybody could ever sing about. Life starts now, with this thought, this revelation, this realisation.

And that's what Roobaroo on Rang De Basanti feels like.

Friday, December 30, 2005

Basanti, music de

That was only until Rang De Basanti arrived. And in the middle of a particularly energetic song, I figured out what had been missing. Rahman, to me, is wonderful when he's disruptive. Disruptive with his beats, with his instruments, when his music is unpredictable. This has also brought about some of his unmemorable stuff, but then, you wouldn't have Rang De...

What a rocking album. More, on what it feels like, soon.

Tuesday, December 27, 2005

Making resolutions that don't hold

Did you know studies show that 98.9% of all resolutions are broken within the first month? Did you? Actually I haven't seen any such studies, but they'd say something similar, don't you think? "Man attempts to give up smoking two packs, gives in by noon," or "Boy resolves to lose four kilos in a month but - dammit! - why do burgers taste so good?"

It dawns on everybody one day, I suppose. I'm sure it will. New Year resolutions do nothing. They're just a spurt of false ambition. But don't let that stop you. No, for everyone else's sake, you must carry on. Everyone else has failed, and so they will be watching you. But they won't be watching to see if you succeed, but to see how long you hold out. Good luck.

Thursday, December 22, 2005

SG and other balls

In any case, you'll find a more detailed explanation in this piece I had done for Wisden Asia Cricket.

Tuesday, December 20, 2005

That rare commodity called air

Meanwhile, it's winter outside. That distinctive nip, that reflexive shiver - not because it's too cold, but because a shiver is almost proof to ourselves that it is cooler than in the summer - they're all here. I cannot wait to be part of it. In a few days, when all waiting tasks have been fulfilled, I'll be huddled over a grill in central Bombay, watching roasting kebabs, and then on a rickety chair on a bumpy street, sharing a table with friends and strangers drawn here for the food. A jacket will be brought out, not because of the temperature, but because the idea of winter calls for one.

All this will be done late, after cars are parked and the streets are empty. A police van might stop to ask what's going on but our satisfied expressions will provide an acceptable reply. There's the cutting wind at Marine Drive, the warmth of the hotel foyer on it, the drifting conversation from the nearby pizza place, the vacant roar of accelerating taxis, the far rattle of railway lines, and the happy thought of a good week gone by, with better times to come.

And it's still only Tuesday.

Monday, December 19, 2005

Hold still, city

Cities don’t change this way. They aren’t supposed to. Clear thinking resulting in immediate action is rare; Bombay knows this well. But Dubai, for three decades, has added one attraction after another. The first attempts involved baking the world’s longest cake and constructing the world’s biggest clock. We, silent residents, nodded our heads in disbelief. But there was the shopping festival, a milking of its own reputation. When that went off well, they had a summer shopping festival too. Malls sprung up quite literally. For many years Dubai had only one mall downtown. Now there were over 15 big ones, downtown had moved an hour’s drive away, and you still couldn’t find a parking spot.

Then there are the cities and towns within Dubai: Internet City, Media City, Sports City, Heritage Village, Knowledge Village and a $3billion Chess City, where each of the 32 buildings will resemble a chess piece. You’ll find Microsoft, IBM, Oracle and the International Cricket Council here, among others. One website called it “The Land of Really Humongous Projects”. The New Yorker titled its feature of the city “The Mirage”. Now plans are afoot for a monorail system by 2008 to ease the traffic, an underwater hotel – The Hydropolis – as well as Dubailand, a theme park twice the size of Disneyland in Florida. It can be quite disconcerting. Old hands will tell you that it’s not what it used to be. New hands will tell you there’s no place like it.

Every month it changes, grows larger and larger, employing more people, presenting more opportunities. A friend, bald from stress, stuck at a dead end job as art director in 2003 was by 2004 driving a blue convertible Mercedes, hair trailing in the wind. In the course of six hours, he said, he went from being fired to starting his own graphic design studio. His turnover in a year was over a million Dirhams (1.25 crore). I’d imagine there are similar stories in town. I’d also imagine there aren’t many places where dreams are fulfilled this quickly. Perhaps in California. In the 1948 Gold Rush.

And what of street crimes in three decades? Somewhere around zero. It’s safe at any time of the day, though my one complaint with the police force is that they’ve cut down their nightly patrol on horseback. That was mighty cool.

But before this sounds too much like a love note, here’s something irritating. Why do people from Dubai always ask you when you last visited and, smiling at the reply, say, “Oh, it’s changed a lot since then”? This hasn’t changed one bit.

An edited version of this piece appeared in DNA on Saturday, December 17.

Thursday, December 15, 2005

An unreal land

Our Man/Woman/Thing Michael [Jackson] has been at it again. Being caught in an Abaya in... Bin Sharmuta Mall. One wonders whether it was an abaya or was it another one of Michael’s oh-so-cool outfits.

One wonders how Michael is coping with this weather. Considering the temperatures in this country, I am surprised his face hasn’t melted off leaving him looking like a uglified Freddy Kruger.

What pissed me off about this whole episode is how the poor lady had to hand over the mobile phone on which she took a pic of good wholesome Mike there. Isn’t this wrong?? I mean isn’t MJ the one who was in the women’s restroom?? I would just like to congratulate the people here on another great show of justice.

This is a post on a remarkable blog about Dubai. It's called Dubai Blog, and if you know Dubai, you'll know that the blog's tagline - 'The most prestigious 10MB on the net" - is a play on the 'prestigious' tag that Dubai keeps playing up. This site is full of insights about how the place works ("Only in Dubai, will you be fined for eating in public during ramadan but can pick up a prozzie in broad daylight with no fear whatsoever" and "Only in Dubai, do they think making copies of the 7 wonders is an "original" thing to do").

The blog was first blocked by Etisalat, the telecommunications authority, before he shut it down. Google has its cache, however.

Though I like the city, it's hard to not agree with this man. There are some very crazy things there.

(Link via Metroblogs)

Wednesday, December 14, 2005

The old city

Things have changed since then. Somebody had enough of this fake Chowpatty business and opened a restaurant called Bombay Chowpatty. A case of the exile’s longing. There was also a Meena Bazaar, a Kamat restaurant – “the same one as in Bombay!” – and some familiar haunts of Pakistan also found their names here. Now there’s a Buddha Bar, renamed “The Bar” after Buddhists protested, in a wholly worldly manner of course.

I love how this city has transformed, but there are few places that I can truly call my own. These are places that still hold on, kicking and screaming, to the past that I remember. There’s the corniche, the promenade that runs along the coast from the massive vegetable market to the stinky fish market and then past the spice market and finally the gold market. A marathon was once held there, and it was a distinctly sticky night. Three minutes after the start it looked like a race for unfit people.

The new Dubai has its cities within the city, but the old Dubai, with its Iranian and Palestinian spice stores, has odors and cheese coloured red, yellow, green, white. A scraggly helper may stop by and ask you to buy “sonfloover zeeds froom Eshipt” and “froom Shina” and “cinmun froom Ceyloon.” In Al Juzoor's natural products people will find on these shelves the answer to nearly all their problems. They have conquered baldness, damaged and oily skin, indigestion, diabetes, and also make bubble gum.

But cheese wasn’t my thing. I just went there because I loved the smells. There were other markets too, and while they lacked the smells, had the atmosphere of Colaba causeway. The textile markets at Meena Bazaar are still occupied by large, cuddly Sindhi seths with mouths stuffed with paan – or something like it, since paan is banned. Close by are the stores of Karama, which would be called fashion street had someone thought of renaming the place.

But quite often, however far I was from it – and in those days you could travel the length of the city in 15 minutes – I would wander over to Automatic Restaurant. Why it is named so, I do not know, and I do not care. They make the finest kebabs in the universe, and serve it with the creamiest hummos imaginable. That’s all that matters eventually.

So it comes down to eating and shopping, two things that Dubai is known for anyway. What’s new? Nothing. No bling, no DKNY, no Big Mac. And that’s precisely why I can’t recommend these places highly enough.

Monday, December 12, 2005

Eating out in Indore

Friday, December 09, 2005

The silent visitor

They recollected the events of the day later. Was anything out of place, both wondered, as if death had moved a vase while it crept closer. Could we have seen it coming, they thought unjustly. Did we overlook something obvious. They spent the rest of that sleepless night and most of the next day asking questions that they could not answer with assurance, for both were now unsure of what they had seen, and what they had failed to see. Every moment that day now held a significance that they did not recognise earlier. Enough hints had been made, they just failed to grasp them. Guilt had begun making a grand entry.

Everything changes from here, they thought without knowing how this would happen. They were right. Change came over them slowly but as surely as death had. Death was long gone but its shadow remained. They learned to live with the shadow, walking around it, stepping into it occasionally. The shadow reminded them of the past. For no reason they would launch themselves into this past, and though it twisted their memories and especially their heart, they jumped in again and again and again. They now expected death to come, bracing themselves for its sudden arrival. They wondered if it would be as surprising as last time. But they did not behave like people who know that death is coming. For that they would need a date, a definite period of living. Expecting death, each day of theirs became numbered. As time went by their senses dulled, and if death visited them as suddenly as it had earlier, it would have been just as surprising. They were thoroughly unprepared.

The day the sky fell in

His sense of smell went berserk. He could not bear to be in the same room as a cup of coffee or a dab of perfume; a roast in the oven or chicken soup on the stove constituted torment. A rare meal he was relishing one evening went uneaten because he got whiff of a sprig of mint. His hearing actually became more sensitive, so that, from the first dose onwards, he hated loud noises; he was never again to get pleasure from music. And the music that resounds clearest in my head is the tinkling of Ward 15's dripmachines, warning the nurses that it was time to take action: "Dee-dee; dee-dee; dee-dee."

The whole thing is here. Remember to breathe while you read it.

Quote of the month, year, etc.

"If a politician contests for a post in a sports body, it is always bound to make some difference. If you want to involve politicians in cricket affairs, then it's better to nationalise BCCI."- Jagmohan Dalmiya.

Tuesday, December 06, 2005

Sampling the street

"Can we stop now?" Abhishek asked as we held each other for support. "I've never eaten so much." I looked at my brother through the spots floating before me. To say yes would have been the right thing, the healthy thing to do. People would have praised our self-control, our ability to say no. But there was something heroic in eating until you burst.

Indore has good food and you can see its effect on people. Belts strain under the weight of meals prepared with no nod to health or moderation. The frantic Bombay walk would feel out of place here. Indore ambles with the satisfaction of a well-fed place preparing itself for an afternoon siesta. And with local cuisine like this, who wouldn't walk slowly?

So we were at Chappan, a street that was busy mostly when skies were dark enough. From everywhere they came to dig into the chaats and pav-bhajis and faloodas and ice creams. Students had come here for over 25 years to announce their results or to reveals their loves or drown their sorrows. New cars were shown off here. A newborn's initiation into the world included a visit to Chappan, which was named after the 56 shops on the street.

Abhishek and I set off to eat everything available on Indore's streets at night. And if we couldn't eat everything, we'd watch others eat while we staggered from one store to the next. Our night of sin began at Johnny Hot Dog, where a counter and two large frying pans separated us from the man behind the counter. "What's an 'egg-benjo'?" I asked as he sliced open a bun and slid it about in warm oil.

"I will put a benjo in it," he answered without looking up.

"So what's a benjo?" I asked again.

"This is a benjo," he said, pushing a plate at me. An omelette in a bun.

"Why is it a benjo?"

He thought about it while wiping his hands. "Because tourists used to ask for a benjo and we didn't know what it was." So how was it a benjo? "The owner called it a benjo because he wanted a simple name for this," he said irritably and walked away.

After getting through the omelette-bun, we strode past stalls of glistening snacks. Empty puris were stacked in pyramids beside large pans of ragda-pattice. Boys with persuasive voices enticed us into restaurants with, "Come inside, sit inside, air-conditioned," and on seeing us moving on, "Okay, no sitting, but standing, serving?" and finally, "Why you are going away? Are you angry?"

There's no escaping food here. You can avert your eyes, but what about the smells wafting almost cartoon-like around every bend and through the car's air conditioner to you? I found myself magnetically drawn from one stall to the next through these smells and sights, presented with new flavours on every plate. Young Tarang's renowned dahi puris were duly demolished. The Bombay Sandwich, the KitKat Sandwich and other offerings were on display. Everywhere people jostled, talking, ordering, appearing confused, looking this way and that - with a plate in their hands.

Dressed up ponies idled by. Balloons strained at their strings beside them. Both were waiting for children. But the children were at the ice-cream shops, standing on tip-toe, smudging the glass display with their nose, picking malai-kulfi and rosogolla flavours. A short walk away was Trupti Juice, where the crowd favourite that day was the sabudana khichdi. This was among the most accomplished khao-gallis anywhere; it had that pleasant chaos which accompanies street food and a polite crowd.

We had reached the end of the street and staggered punch-drunk, considering if our best interests lay in going home, when Abhi suggested, "Falooda?" It turned out Indore had not one street of food but two. If the main course was at Chappan, it had to be followed by dessert at Sarafa.

Sarafa is an alley in a district of alleys populated by low-lying buildings, with electrical and television cables criss-crossing from buildings to poles to other buildings. Most streets have enough space for only a car and a half to pass through, and it was one such street we traversed, honking furiously at - predictably - the only cow I had seen that day. Beyond the cow lay a street of downed shutters. During the day cloth, utensils, and knick-knacks were sold. At night, for nearly 40 years, in front of these shuttered stores, entrepreneurs set up stalls selling jalebi, rabdi, falooda, gola, paneer chilra, gulab jamuns and malpoa. Above these were homes, and faces peered down from balconies to follow the action.

Thick sugar syrups bubbled over open flames, men stared dourly into their frying pans, turning over sweets with one hand and handing customers platefuls with the other. I wandered past most, too full to eat, and also eager to move away from the stifling heat of this outdoor kitchen. But others preferred to stay here, sampling this and that, impervious to the blast of hot air. I found the falooda-walla with the help of a local. Indore's most famous falooda-waala was beside Indore's best malpoa-waala, who was a short distance away from Indore's most renowned gola-waala. This street was a who's who of snack-makers. It was tempting to grab and run.

The falooda was everything I had imagined it would be. It wiped out every other taste, negated heat and discomfort, and instead melted the eater. It was food that made everything okay with the world. For less then 20 bucks, all this. This is a town of cheap eats. As we packed up to leave at midnight, having eaten out for five hours continuously, Abhi stopped at the car door, stared intently at the grimy road below him and said, "That bloody gola-waala. We didn't have his gola," and bounded off after buckling his belt to complete what we had begun. I don't know if it was a foodie thing or an Indori thing.

No small matter

Do browse through his pictures. Many of them are delightful, especially the ones taken in Mahim. And while you're at it, check out the first photo of his 'Bombay Breakfast' feature. Many of you would have heard of him already since he's been about for over two years. But for the ones who haven't, here's Trivial Matters.

Playing games

But listings are tough, numbing work. I imagined clubs and sports bodies would have their schedules ready to fax to the next interested person. The difficulties posed in the search for a schedule have been revealing. I will explain in great detail why this is so. Consider this conversation:

(Sfx: Phone ringing.)

Phone: Click.

Voice: Police Gymkhana. Who is this?

Me: My name is Rahul Bhatia, calling for Time Out…

Voice: What do you want?

Me: I’m calling from Time Out magazine. I need your schedule of sporting events for December 2-15.

Voice: Why?

Me: Because there is a listings page…see, this listings page tells readers what’s going on in the city, you know, like a cricket match next week, or a women’s hockey game on the 20th. That kind of stuff. It’s to inform readers, so that more people visit the event.

Voice: Achcha. Give your number.

Me: My...what? What? Why?

Voice: Give number. To check.

Me: Check what?

Voice: To check.

Me: (Skepticism rules) You will call me back? Here it is…

We hang up. A while later the phone rings.

Voice: Yes Mr. Bhatia, you wanted our schedule…

Me: (Full of hope) Yes? Yes!

Voice: Mr Bhatia, I cannot give you. Is classified.

Me: What? Why is it classified?

Voice: We don’t give.

Me: So how will people know what’s happening at the club?

Voice: No one knows. We don’t tell.

Me: (Losing composure completely because it has been a long day filled with similar conversations) You’re mad. You’re completely ****ing mad. What the hell is classified about what you do? The Police Gym is on unfenced land at Marine Drive and you play matches under floodlights. People on passing trains can see your club, people can walk across your ground without restriction. I can come by to sleep on your grounds. What the hell is so private…so classified about that? It’s only sport!

Voice: We do not usually…

Me: Forget usually. Make an exception and tell me. Just this once. I won’t bother you again.

Voice: (After a pause) OK. I will tell you.

And so it goes. This is only one conversation, though it is one of the worst I’ve had. Calling up clubs, if you haven’t done it, is a bit like being next to the repetitive receptionist in the movie Office Space. It is quite possible that many potential spectators, faced with the obstacle of official hostility or, worse, official ignorance, might ignore sports they would have otherwise visited. In some clubs the sports head is known to nobody else. In some the schedules for the following week have yet to be drawn up.

But there is something else I’ve noticed. While the official apathy seems to permeate through most sports, there are individuals who become magnets through their passion for their sport. Athletics and billiards have such followers at their disposal. Motor sports seem keen to have more fans.

The rest…the rest just go on, from schedule to schedule. A call for information arouses several suspicions, and they will only proceed once they are convinced your intentions are not villainous. Exposure is not something they evidently require, the information has to be an exchange, rather than a given. I’ve given up doing the listings. There are too many people who need reassuring, too many who, once reassured, cannot reassure you about what they do. Sport needs new hands.

Update: Correction - Not 'new hands', but 'more capable hands'.

Sunday, December 04, 2005

Far too suddenly

People fly away for the summers, they return when it is less uncomfortable. I would do the opposite. My summers should be summers, and winters filled with snow. These days there is nothing, but that is not my complaint. December has just begun, and there is time till we bring out the sweaters. If it snowed I’d lie there for hours staring at the sky, watching people pass me by, asking, “Why?” And I’d tell them it’s easy to see, it’s cold to touch but it’s soft to feel, and when I want to sink in it accepts me comfortably, and from here the view isn’t of land or sea, but the open expanse of my dreams.

I don’t mind snowballs but they aren’t my aim, neither are snowmen, I’d only do funny things with their carrots. I’d watch fresh footsteps in the snow, watching only humans tread where rickshaws hesitate to go. Snow leaves its mark, snow traps warmth, and the whole city would move in clusters of bodily warmth. But there is no snow, so we move separately, waiting for a winter that will pass by us far too suddenly.

Saturday, December 03, 2005

Words

Anand Vasu, a colleague, chatted with Pawar after the BCCI's elections were won. He came away with an interview that was optimistic but grounded. Pawar had in mind a cricket board that functioned effectively, had good facilities, worked not only to make money but to return it to the game, and was also transparent. He would try to convice members that adhering to the board's constitution was in their interest.

Have you visited an Indian cricket stadium lately? Most grounds need everything that Pawar spoke about. They would improve not slightly but dramatically if he walks the talk. Now the BCCI owes me nothing. I may be a moral stakeholder but cannot impose a desire for transparency and improvement on the board. One can only hope. But with Pawar making these noises, it seems too good to be true. It seems almost naive to believe what he says, and yet one hopes.

Yes, it is probably naive, but this change in regime could be good for the game. There's nothing to base this feeling on except words, but words are where most things start.

Wednesday, November 30, 2005

On the run

When we last spoke to Sairaj Bahutule, then Mumbai’s captain, the Ranji Trophy semifinals were close at hand and the mood was optimistic. The team was unbeaten, batsmen were in good form, and they were tipped to win, as Mumbai are expected to every year. Dominance, form, history. How much do they really guarantee? Punjab snuck past them.

A few things changed since then. Bahutule left for Maharashtra. Chandrakant Pandit, the coach, just plain left. The newspapers went to town. The subject is not up for discussion, Bahutule says now, there’s no need for controversy. So we talk about Mumbai’s last season, its history, and the future.

“In seven league games we played exceptional cricket,” he says about the campaign. “I think it’s just one of those things. But the guys had applied themselves and I think it’s one of those years when some things are not meant to be.”

Railways, a group of players unfamiliar with luxury, eventually won the title. In the days that followed, they said that their big incentive was a better life. So what incentive did Mumbai need to achieve success? “Mumbai cricket has started the gradation system, which is very good,” Bahutule says. “I’m sure it’ll boost the players’ morale. A lot of talented players are still there and I’m sure they’re going to push themselves and get into winning ways. It’s just that we didn’t win last year. Otherwise out of three years we won two. So it’s not a bad record at all.”

One of these young guys, he says, is Vinit Indulkar. At 20, he scored nearly 500 runs last season, his first one. “He did very well in the league stage, and didn’t get runs in the semis, but obviously that’s just one odd game. He’s a steady guy, a level-headed fellow, works very hard, is focused on what he wants to do. He’s got a good future.” Good enough to wear blue? “I think so. I believe he will.”

Mumbai no longer produces stars as it once did, and no longer wins big as it once did. Has Mumbai’s grasp, on the Ranji Trophy especially, slipped? He pauses momentarily. “To be honest I don’t think it has slipped at all. It’s just that certain performances, like a batsman getting 1200 runs, have not been happening. 1200 runs is an exceptional performance and selectors at the higher level cannot ignore it. Our guys have been getting 600 or 700 runs, which is good, but not exceptional. So that’s where we have been lacking and certain other states’ guys have been faring exceptionally well.”

Vinod Kambli’s absence made a difference. Hair, attitude, the whole package; you miss the runs, you miss his presence. When he plays, the difference in morale is palpable. Bahutule says this is true of the international players. “Even when Ajit plays for the team, the morale of the team just goes up. Basically the guys feel, ‘all the international stars have come in’, so they push themselves a little bit harder. All the youngsters try and learn a few things.” And when these guys retire? Then what? “Whatever these guys [the veterans] tell them, they have to register in a way that they take it along for the next ten years and give the same [advice] to the youngsters who are going to come after them. That’s been the thing with Mumbai cricket. The guys who go off leave their experiences and memories behind, and it’s up to the youngsters to take up the attitude and move forward.”

When he takes the field for Maharashtra, Mumbai, who have played him for 14 seasons, will have begun comprehending life after Bahutule. It should not affect the team, he says, for this has been a strength consistently. Players come, players go, but the focus remains the same. “I started off under Vengsarkar, Manjrekar and then Sachin, so all the players who have played for Mumbai have been very aggressive, very focused and have been motivating cricketers. They had an aim: to play for the country.”

A sleight of mind

Looking for magic is a bit like looking for romance in travels. Not romantic love, but the romantic notions of travel. Both – looking for magic and traveling – set out into new territory seeking magic, but it is the traveler who is more likely to understand first that magic is occasional and that there is little sense in waiting for it. The journey itself is so tiring, and the experiences so varied, that he is resigned to the fact that magic may not come along, but regardless of this the travel must continue because of everything else it provides.

I haven’t traveled much but the mention of a journey has, for the longest time, set off the imaginative machinery in my head. The romance of travel existed only when the travels were imaginary, the magic existed only because I created it. When the time arrived to physically do it, the endless packing, moving, seeking, avoiding, refusing, catching, clutching, listening, talking, there were only traces of magic, but the experience left me richer, as if perseverance was rewarded with a country revealing itself to me. The more I dug, the more it would give me. Skimming the surface and waiting for the romance of far-off places meant ignoring what lay beneath. Romance didn’t stand a chance.

Magic is no doubt seductive. It whispers in an ear and disappears and, in an instant, you know what the world could be like for you. But reality, I think, though lacking daily magic, has something potent too. It offers experience and learning with no pretensions or deceptions. Life, as it is, is provided as proof that there is more to life than simply magic.

Tuesday, November 29, 2005

The plain dealings of the Bharwad

One day while driving through the Dasada village, I spotted two Bharwad men holding hands as they ambled along. They were dressed in white, wore turbans, and jewelry dangled off their head, neck, ears, wrists, and around their waist. The waistbelt was interesting. Held together by silver link chains, old coins with profiles of King George and Empress Victoria dangled at regular intervals. Watching me, a guide spoke up.

"They have to wear this. It is important."

"What, this waistbelt with the coins? Then how come the others aren't wearing it?" I asked him, wondering if forgetting to wear one resulted in unpleasant things.

"No, no. They have to wear jewelry. Like ladies," he said, and settled into his seat.

This seemed to make sense to him, and I'm sure it was clear, but I imagined right then a gay tribe.

"Look, are they trying to be like ladies?"

"Yes, but not like ladies. They have to wear jewels to attract ladies. In September they stand below an umbrella and ladies will maybe go more to whoever has more jewelry. They go and stand under the man's umbrella and - foosh! - their marriage is over."

"They are married?"

"Yes, their marriage is over."

Blimey. Right then I was surprised by the simplicity of it all. No talk of magic and connections, or angst about family ties. Just like that the deal was done. The shiniest man was the most attractive. What a wonderful culture, I thought, and glazed over into a mellow mood.

Back in the city, it doesn't seem all that quaint anymore. People dress well, people earn money, and they attract a mate. The difference is it's a little more obvious in the village. But there is one other crucial difference. Since women don't know how Bharwad weddings are done, you can invite them under your umbrella. While they think about chivalry or whether you're just being slimy, you can snigger knowing that you've just got married.

Winters in DUMBO

Over a few winters, I watched it change from a private enclave into something larger, more moneyed, and decidedly commercial; this was, after all, in keeping with its past. The year was 1999, and my professor, Michele Washington, sought an apprentice, while I, a student, was in need of a job. We shook hands and smiled, and I was struck by the considerable thrill of personalizing the relationship between teacher and student. We did not discuss money, instead she advised me on how to find my way to her office. I did not know that business was done this way among a few in DUMBO.

The first time I visited the place, a biting breeze blew through narrow lanes over cobbled roads from the East River and up the slope I descended. The street ended at the Manhattan Bridge, an extraordinary sight. Along it, tall brick buildings were set into neat blocks. These were the Empire Stores, large buildings that stored imported goods when the place was an important port. In the 70s they were declared protected structures. Now they are lofts, studios, and office space.

I found the office, a quaint graphic design studio in an abandoned warehouse, and worked there for a few years. Other tenants would stop by. Down the corridor was a wood craftsman who carved tables and cabinets with delightful care. Above, the proprietor of a web business worked several hours everyday and stepped into the next room, home, for sleep. We designed identities for them. They did things for us. This, in a sense, was what DUMBO was about. It was a familiar community of artists and small businesses, of people who stopped on the street to chat, who visited for coffee on a cold evening. It was a comfortable enclave. Of course it grew. Galleries sprung up, prices went up, everything went up. Undersized studio apartments overlooking the river and Manhattan sold for $600,000. A store dedicated to healthy eating was overrun every evening by painters, designers, and those who liked banana yoghurt.

In a few winters the glitz began to show. Building entrances were widened and made more alluring. The area began to revel in its bohemian skin. Artists were forced out by costs, but DUMBO once again grew prominent. The people on streets were more varied, but its pace remained constant. With the Manhattan Bridge as their wallpaper, Manhattan the view, and its graffiti like paintings, it had become a place to be in.

Monday, November 28, 2005

The world underground

The subway is a frightening place. The stairways are often lonely, the slightest shuffle echoes eerily across empty platforms, train windows are bulletproof but have holes shot through, when an oncoming train's lights penetrate through the dark tunnel before it appears it looks beastly, and there are drunk travellers muttering to themselves. As a student there, I traveled underground. There was no other choice. Buses were too slow. The train was the popular, if feared, vehicle of transport. ‘Rule one for the subway is,’ Paul Theroux wrote, ‘don’t ride the subway if you don’t have to.’ Since hailing a cab was a luxury to be enjoyed only in the distant future, students rode the subway because they had to.

The universe of the subway and that of above are separated at the station’s entrance. Some New Yorkers have never traveled here, having heard stories as if it were a foreign place. Even foreigners who have not tread in America offer a word of caution about the subway. It may seem presumptuous, but the stories are somewhat true. The rats are huge. Commuters are routinely mugged. It is safer to travel in groups and blend in with locals. It is advisable to never get lost. Being lost could mean the difference between Manhattan and the Bronx. It is a big difference.

And yet one must travel by these trains. New York has its sights and clubs and museums and shopping, but where else does one see a system that runs parallel to the one above? Both live uneasily beside, and rely on, each other. It is another face of a many-faced city.

Anything but a drag race

And then there are the drag races. I had first heard of them through a whisper, as news was often spread then. Now, well now is different. In Umm al-Qaiwain, a few hours’ drive from Dubai, is a drag race operation that was once illegal but now conducted openly. Here large numbers of Arabs gain and lose expensive cars. There are many, many cars. Fancy German automobiles, the Nissan Maxima, Japanese off-roaders. The supply is endless because the money is endless. The sons of the wealthy and influential make appearances here regularly, and boost the currency in these transactions. There are stories about these events being backed by powerful families, and the cars themselves encouraged by nitrous oxide. But at the heart of everything lies the race. Find a way to visit one. Here you find a few things that drive Dubai: speed, power, and money.

Sunday, November 27, 2005

Doing the Konkan coast

At Alibag, the mood was contemplative, and the sounds were muted. This is what one saw: bored horses standing by, tied to rocks, while their runners viewed the rare visitor with undisguised disinterest. A few dots, people, bobbed in the sea. Stretches of beach were occupied by only dog and crow. Hotels otherwise used to activity are quiet, taking a breather, before the season begins. And this is otherwise a weekend retreat. Even the Kolaba fort, floating nearby in the sea, was made inaccessible by a rough tide. So with history and colour both unavailable, a day here was enough.

This was an unpleasant start to a Konkan beach trail. It hinted that squelchy beaches and deserted towns lay ahead. The reason for setting off then seems foolish now, but here it is: some choose to walk in a garden, some choose to walk down the Konkan coast. Also, one does not find ruined Portuguese forts in the neighborhood park.

An hour’s ride south of Alibag, past open fields, an area of dense vegetation appears. Trees curve over the brown road from either side, and homes are camouflaged by a barrier of green. There are no sounds but the bus’. This is Chaul. Not too far from here, down a winding road that turns into a sparse market, and then beyond it, is Revdanda. There is a beach here, clean and quiet, unoccupied, with a view of the hilltop Korlai fort in the distance. Behind the beach, beside the Kundalika river, is an abandoned Portuguese fort overrun by vegetation. The roof of St. Francis Zavier’s Chapel has fallen in, and its walls are caked in moss and creepers. A large stone slab lies at the entrance, with a seal and a message carved on it. A story describes how a visiting Portuguese historian came by it, knelt to brush the moss off with a toothbrush and, upon reading the message, fell back in delight, scarcely believing its value.

It is now a sleepy town; so sleepy that during afternoons the town’s police force is found asleep on benches and desks in the station. Nothing happens here. On average, a solitary crime is reported every month.

Then, normal service resumed. The bleak sights of Alibag played themselves over and over, beach after beach. Murud-Janjira was uninhabited except for a horse-cart and five fishermen untangling their nets. The tanga-waala offered a ride and the harried story of the off-season for people whose lives depend on seasons.

At Ganpatipule the sun shone on the quiet temple town and its vague myth. Its streets were empty, its inhabitants were at home, and visitors were a few months away. Inside the luxurious temple glittery ceremonies were conducted with noise and dedication; outside there were religious reference books on sale. Here a priest sidled up and announced that a circuit of the hill behind the temple would bring wishes to life. Atop the slippery moss-covered hill, at the end of the circuit, another temple hand declared the exacting round incomplete unless a monetary donation was made. Below it was a glorious white beach and a roaring black sea. Both were empty.

A hop across Goa (too done, too done) to Gokarna proved futile. Along the way, animal skulls were placed on thin wooden sticks in the middle of fields. Adding to the overall strangeness, faceless scarecrows launched off rooftops, arms raised to the sky. A road was washed away. And boy, it rained. Drops pattered relentlessly on the eardrums of Gokarna. When things go wrong, in hindsight the omens are everywhere. Rains had swallowed the beaches. By this time rains had swallowed Bombay, too.

Misery had begun to sink in. Of being on the road alone, of waking up in desolate beach towns. I pined for a traffic jam. Traveling here in the low season was to know a particular kind of helplessness: like attending a circus without performers, animals, and the band. Where were the people? There is such extreme solitude that it is disquieting.

Friday, November 25, 2005

Hello and all

Letting go

Haroun Kamal

We were young then and so we never saw it coming. All we knew was that South Africa were the team to beat in one-dayers because they played the game in a supreme style called ‘total cricket’. It was so clinical and so very effective, no one, even experts at home, knew what to do. Maybe individual brilliance, maybe bad umpiring, maybe others would catch up. But they were such a long way ahead. They had an effective captain – a popular born-again Christian, no less – their fielding was exemplary, and the bowling was in tip-top condition. When they played India, everyone prayed a little harder.

In two years, from 1995 to 96, South Africa met India in seven matches before the Titan Cup final at Wankhede Stadium. If we restricted them to 223, they kept us to 209. If they batted first, India’s chase was futile. No use. Forget about it. Even Tendulkar played the game at the pace they set. Then, on one particularly sweaty November evening, we beat them in a match that counted. It was the final of the Titan Cup. Tickets were sold out, there was the usual murmur over the seats allocated to clubs, India had just scraped past Australia to qualify, the Man was in form and, amid all this, something told us yet again that it was India’s day. So squeezed together tightly on sagging wood benches, we watched as the afternoon began with Sanjay Manjrekar scratching about in his last game, a little while later it was all Tendulkar, and then Anil Kumble ran away with the stumps at night. Wankhede exploded in a burst of giddy cheer, and for a few days the mood was distinctly post-coital.

Then we won a rollicking Test series, and ended the 59-day tour by winning the hastily-constructed Mohinder Amarnath benefit match – an official one-dayer – at the Wankhede. The last game was an excess; the visitors were disillusioned and pined for home, and Cronje vented his anger on a local official. That, nine years ago, was the last time the two met in a one-dayer at Wankhede. That last game, part of neither a series nor of significance, was forgotten for four years until it returned to memory with such force, that it is unlikely to be taken for granted.

In 2000, South Africa were back, and better prepared. India, distracted by captaincy problems, were soundly beaten at home for the first time in thirteen years. A week after the victory, Cronje spoke to a man named Sanjeev Chawla. The Delhi crime branch tapped phone lines and overheard as promises of runs and wickets and low scores and cash were exchanged. We now know matches were altered. We know Cronje accepted money. We realise many people were involved. Match-fixing is not accepted, but the idea that it exists, is. The cynic within acknowledges that it is always likely. That is what the revelations of that year did. They woke up those who didn’t know better.

When Cronje finally confessed, specific matches were mentioned. The benefit match in Bombay came under the scanner. Before the game, Cronje had made his team an offer. Gary Kirsten, a senior member of the side, described the moment in his book. “’We have been offered a lot of money to throw a game,’ he said. I swear you could have heard a pin drop at that moment. Nobody moved a muscle. In retrospect I think I had gone into instant shock. I listened but it was out of respect for the captain and a strange fascination with what he was saying rather than any intention to carry out instructions. I knew within a few seconds I could not be involved ... but I listened… He mentioned a couple of times it would be worth 60 or 70 thousand rand each.”

Cronje was sacked, barred from the game and cast out publicly. Shaun Pollock, who became vice captain after Kirsten stepped down from the post in 1998 without explanation, became captain. When Cronje died, Pollock dedicated a victory to his predecessor. The next captain was the 22-year old Graeme Smith, who was less involved. “I never met Hansie Cronje. I never played with him or against him. He was a good leader but in the end he tarnished the game.” Step by step, captain by captain, South African cricket was detaching itself from the effect Cronje had, and ensuring that a new leader emerged from his huge shadow.

Five years is a long time. Since then India have caught up with South African methods, especially in matters of training. Since then one coach has come and gone, and the next has already made his mark. Since then people gained interest in the game, lost it, and recently regained it. There is a new captain who bats like a dream. His counterpart, Graeme Smith leads a team that has had some success. The focus is likely to be on cricket, but perhaps that is unlikely as well, because a couple of weeks is also a long time and anything could happen. Television rights, board elections, backroom politics. All this we can deal with. But it is the silent thing, the unspoken issue, that we will try to forget when South Africa arrive without Herschelle Gibbs and Nicky Boje, who investigators would like to question for what happened back then. And because of this absence, while both teams look ahead, the past clings on, unwilling to let go.

Saturday, October 15, 2005

See you soon

This won't be a long and winding goodbye, so wait, I'm getting there.

Before last December I had written very little, so this blog helped me catch up, and proved to be an emotional crutch as well without getting into the 'dear diary' kind of writing. It also helped discover limitations, eg: Ability to write about roads and driver behavior: good. Ability to analyse merits of libertarianism over lefty ideology: bad. (So bad that I've probably got that bit wrong as well.)

But while it has been fun, I reckon it's time to say bye and get down and write for a living. Like anybody out there who can hold a pencil, I'd like to write a book someday. And travel, and sleep well, and never worry about money. So it's time I got started.

Goodbye. And see you soon.

Friday, October 14, 2005

"Sasta hai, madam"

“It is not about the prize money. It is about winning a place in the India team, which is worthless.”

I'd imagine Javagal Srinath, the former Indian bowler, meant to say 'priceless'.

Tuesday, October 11, 2005

The oppressive Indian

Bansal found herself inundated with crass messages from overnight blogs before her readers began to weigh in their support. The offensive comments ventured nowhere near fact, preferring instead to silence her through fear. The threat to burn laptops was another intimidating measure to enforce silence, and there are some victory celebrations now that Sabnis has resigned. That is a misinterpretation because Sabnis left in support of his ideas, and has found favour widely for his behavior in this matter. The alternative, to remain quiet and withdraw his opinion, would have been easier and understandable given the stakes involved. But the only way to keep speech free is to defend it, and his departure is part of that defense.

So this is an offensive to suppress truth and a dissenting voice. It is not surprising but always worrying that people choose this path. And so, further and further we slip into ignorance, not knowing the truth, not given access to facts that are our right to know because they are buried. However, the events of the last few weeks have been recorded, for posterity and easy access, as well as the aggressive manner in which the IIPM has approached argument, and the support Bansal and Sabnis have found from friends and advocates of free thought and speech. The IIPM's conduct has been despicable, for if they have not told the truth people have suffered to find their efforts and investments coming to little, and if they have not lied, their handling of this situation has been in poor taste. The internet is perhaps the last place where free speech is understood, respected and appreciated, and is a place beyond the reach of IIPM's marketing clout. If mainstream media raises the issue of speech and truth and moves on, as it must, an archive of these happenings will remain here. That these words exist at all, that this dissent is there for all to see easily, is a significant win for those who speak freely and truthfully.

Give Bansal and Sabnis all the support you can. We all need it.

A wide range of supportive opinions are to be found on India Uncut, Kitabkhana, and Desi Pundit.

Saturday, October 08, 2005

Trippin' on books

I asked a librarian about old books, very old books, say, first-person accounts of life in...

"They're over there," he said, pointing at a large doorway before I could finish. "But for members only."

The members-only area was where elderly Parsi gentlemen sat over cups of tea and discussed misfortune on leather couches. Busts stood guard occasionally, stern English figures gone decades ago. This was, however, only the common room in the members' section - a large hall which connected to the other rooms. One wall was lined with metal filing cabinets that noted the author or the topic. And this was it, apparently. There were no librarians, just filing cabinets to help you find your way around. A bit disconcerting if you think about it, especially when the secretary (of the library, as opposed to Miss Paulomi, who takes notes and files her nails all day) says to you 'we've got everything,' with an emphasis on everything. Everything? I ask, mouth slightly agape. Everything, he repeats, shutting his eyes in conclusion.

The shelves are dusty, and I find (to my delight) that books such as 'Two days in Cairo' or 'A journey into the interiors of Africa' have very few spellbound. I remove one such and it nearly falls apart, its glue having lost its stickiness. The pages are brown, with a darker brown creeping across words on some pages, and dust flies up when I flip through the book. There are shelves and more shelves full of these books. Shelves that will need a ladder, shelves that will take years to explore. I decide to join this library.

But wouldn't you know it, there's a catch. Two members have to testify for your character. Normally this would not be a problem, but someone has recently been caught walking away with pages torn from a valuable book, and the people who testified for him are now in soup. After approaching several visitors, two, the secretary and an eccentric swami, vouch for my standard of writing without knowing me. I thank them and am about to pull my hand away and leave when the swami squeezes my hand and orders me to follow him. What follows is a tour suited to a Manhattan office in speed as we climb down spiral stairs into the 'godown' - "Manuscripts, old old books, very old books, microfilm, binding room, tremendous old books here." - bounce back up and into the study area where I am introduced to researchers, and through another cavernous hall before entering the newspaper area where, I cannot help notice with some glee, stands an enormous bookshelf titled 'Travel'.

All the books I cannot have and have yet looked for, and a number of books I don't know yet that I will eventually need, are all here.

I don't know. This place, Bombay, has suddenly begun looking good again.

Friday, October 07, 2005

Inverted city

Well, there are few people visible. They stay out of each other's way for the space they have is a precious thing. In physical terms, your space is space - the area you occupy. Expanding it, your space is the place you carry with you to think, to react, to initiate. You can see it around the people of this city. Because of this, in a sense, the lack of a crowd highlights the individual. It seems the right way to look at people. Not a crowd, not a mob, not a teeming mass, but individuals. We are primed to take in crowds; it is a way to not be overwhelmed by so many individuals at once.

I'm not one for crowds. Well, sometimes. When they aren't being too jostly and getting in the way. But we all seem to be getting in the path of somebody without knowing it most of the time. So you could be irritated or apologetic. You could even be indifferent, but let's see how long that lasts. But with no crowds about, as in the quiet city, there is a feeling bigger than the instant obvious freedom: that of a freedom of expression. It is a blank canvas that stretches as far as you can see.

And so it is with some cities. When the clutter is removed, you see it for what it is. There's even optimism that by cleaning it up, by removing the clutter, you can make it even better this time. To see this city, the one that leaves you with hope and cheer, drive about Bombay at four in the morning.

Thursday, October 06, 2005

A movie that moves you

It's not everybody's preference, but silent men who hide danger beneath a suit and practice martial arts and drive a shiny Audi past bullets without even a touch make for a really fun movie. Plus there's this evil woman in her underwear who fires machine guns. Then there's the unbelievable plot - a deadly virus, etc. - a villain who, we are made to understand very early, is an ultimate fighting machine, a car leaping off a parking high-rise onto another building, a crashed learjet, an underwater fight, a massive black killing machine who is smothered by a falling boat - oops, I'm not giving away the plot, am I? Well, lies told often enough become the truth, and so it is with unbelievable things. Everything starts to make sense. A chandelier hook a deadly weapon? Sure! A car flies upside down to detach a bomb stuck below it? It's really possible, see? It's that kind of movie. Stepping out of the theater is anti-climactic. There are no chase scenes, no gun fights, everything's just too...usual.

Sunday, October 02, 2005

Choice of life

But it doesn't all flow that way, does it? What I'm worrying for, if you haven't figured it out, is myself. The idea is to be someone, to rise and rise in every way possible. To be among people but to soar. I suppose there's always weed for that but it isn't really my scene. It makes my head spin. It's a life within reach, always tempting, always whispering seductive things to encouraging ears. The way I see it, this is how it works: there's a part, I think it's the brain, that says, "Go on, mate, leave this place, go away somewhere, make a living, be somewhere where the taxes and petrol are cheap, and you don't have to worry about books or wines." And then there's the voice of conscience, the broken voice of the hard life that says, "Money, money, money is all you ever think about and you will be happy but will you be happy knowing that you could have done something but didn't, and instead followed a family into the life of safety and security, where paunches grow behind jingling cash registers while wives stay at home? Will you resist the certainties of money and grudgingly accept the insincerity of life? It's a bitch, mate, I know, and it's also a path of ruin, but it's really worth it. Think about it. When the make a family tree, they'll have a special mention for you: The guy who did it differently. Of course you might just die anonymously in a cardboard box somewhere. And there may be no family tree."

So this is what I'm up against. What's the hard life like? Well, it's a pain, really. Bombay's hard, for instance. Everything's hard. Watching the road look different everyday is hard. The lights going out is hard. The water going out is hard. For some reason I've stopped buying into that 'but there are so many people worse off than you' argument. It's rather pointless, I think. Don't you? The point is, when I'm feeling miserable I'm not thinking about anyone else. It's my personal misery. Dammit, you'd think this is the one thing you'd have to yourself, but no, apparently this needs to be cut up into neat slices and passed around too. Everyone gets a bit.

Where was I? The good life or the hard life. The good life might be hard to take in a different way. Say I take it up, and work at it for 25 years, will I sit back and think 'my god, you oaf, just what were you thinking at 25? Why the, you sod, why the hell didn't you take the hard life?' What makes it harder is when I think of the hard life, I think of Indian women in ethnic skirts. It's like this, and this might be a madness of sorts, but hey, you don't come here to subscribe to sanity do you? Do you? Anyway, it's like this: in my mind, women in ethnic skirts are dusky, wearing bronze necklaces and bracelets from different cultures, they are 'in touch' with themselves, and because they are in touch with themselves, they look beyond money and a fancy toaster. For a few years now I've had a woman in an ethnic skirt on my shoulder where an angel or devil should be. She's my financial and spiritual adviser. Oh don't look like that. Everyone's got one. I'm sure of it.

On the other hand, she could be absolutely wrong. You know, the path with good intentions, and I know where that leads. So it's a funny thing to be caught in. Knowing your options are open but being paralysed by choice. I read somewhere that instant decisions are best not left to the democratic process. It feels that way a bit at the moment. Too many voices, too many choices. I have to make this decision soon. It feels odd to stand at a crossroad.

Friday, September 23, 2005

Adrakchai

As always, it's raining outside and drops are sliding down my window lazily. There are hundreds of streaks like this, and of dried lines as well on the large glass pane. The concrete below is dark green and the building opposite is dry and wet in places. Beneath some parapets pigeons sit quietly and watch the rain. There is the noise of a busy world from far away, but here everything is nearly still. Right now, a watchman walks by dragging his bamboo stick behind him. Besides him nothing else moves. It's another quiet, contemplatively gray day in Bombay, and just right for a hot cup of adrakchai.

Wednesday, September 21, 2005

A motor

Each recent month had brought with it hours of lost power. And there were the disasters, the burst cloud, the collapsing buildings, the confrontations between politicians who were once united, the bar girls. Each day greeted us with a sympathetic smile, and I am certain others felt this as well. It's been a weary summer. The experienced say it was always this way, that this regression is new only to you foreign-returnees. They smile and pat and say "keep going" because the city hasn't collapsed, they say, and their lives are better than they were some years ago and they now have broadband and supermarkets and modern cars, they say. It isn't comforting because "life is better now" says nothing. A smooth road, clear drains, uninterrupted power will say a lot more. It's a place to start.

I don't feel like dancing now. Perhaps tomorrow morning will be better.

Monday, September 19, 2005

The murderer

The corridor on the second floor was a collection of bored accused, listless constables and smug lawyers. It was strangely chilling to realise that the accused had faith in justice. In many cases, my prejudiced eye had convicted most of them already. There was another discovery, and this brought a rush of panic: the courts branched off the corridor just as classrooms did in school; the colours were familiar, the smells were of the same musky academia. And the manner – how everything came back so suddenly, so quickly without warning! – the manner in which the judge faced the rest resembled countless colourless lessons. The real terrors that school held returned then to affect me in adulthood, and they had grown in ten years to adult proportions.

A bald lawyer with wispy red hair in Court No 4* represented a man accused of possessing 160 kilograms** of hashish. The end of his flaccid nose sloped downwards past his upper lip when he smiled, especially when the sneer followed a question to a nervous anti-narcotics officer. One such instance, when he smiled at me, I looked evasively to his feet and saw, beyond them, a large rock. In a room of straight lines, it stood out as a physical anomaly. For an instant I could see nothing, no judge, no court, but only the rock in violent hands, brought down repeatedly for dramatic effect. A nearby constable confirmed that it was indeed used to take a life. And then I noticed the other articles of evidence lying below the desk near the witness stand.

Bundles of clothes were stacked against the walls – further evidence? – and the ground was dusty. Rusty green filing cabinets stood between doors, and the windows above were opaque now but, one sensed, transparent and less foreboding years ago, when this building was new. And now, though it was known as the ‘new building’, its age was lost in wrinkles.

The courtroom could have been the corridor; whoever wished to observe the proceedings could do so, and could leave when they wished to. If they chose to stay, this is what they would have seen: every question, every answer, was followed by a long pause as the judge dictated words to a stenographer troubled by his accent; the narcotics officer clenched the railing of the witness box when the lawyer questioned his version of events; the lawyer did not know his client’s name, once correcting himself, “Mr. Pringle…Mr.Pingley…whatever his name is.”; and around me the accused sat hand in hand with the police as they waited for their version of justice. Here I felt as helpless as I have ever felt, more than death visiting because death was over in an instant while the court decided the turn lives took, and the courtroom, I realized, was a place not where the sharp distinction between guilt and innocence was found but where the lines blurred.

As the argument continued, a figure sat by me and shuffled closer. “Are you a reporter?” he asked. I said yes, to which he smiled but said nothing, sensing I was preoccupied. It struck me that the people here were not picnickers, so I asked him what he was doing here.

“I am here for murder,” he said with a warm smile. The smile did not soothe the raised hair on my neck or the tightening stomach knot. He used his hands – his free hands – descriptively as he spoke of exactly what the case was about. “This man, this judge,“ he said, “is an idiot. Look at him. He’s joking with the lawyer while we’re waiting for him.” He swept his arm across the bench where there sat a Nigerian, two men in salwar-khameez, and a slight man surrounded by three constables. He repeated this loudly, attracting attention to us momentarily, and I asked him to softly explain why the judge was an idiot.

His reasons were grudging for repeated bail applications had been rejected, and this time was no different. After he made his plea, the judge dismissed him with a wave, and his reaction was surprising. The accused turned to me, grinned through a beard and winked before he was led away, as if he had expected an outcome no different. I understood, but it was an understanding of a different kind. Between the creaky cabinets and unused clothes and open evidence, there didn't seem much space for justice.

*In my interest, the court number's identity has been protected.

**Also, the amount in kilos has been changed, though the actual amount is larger.

Wednesday, September 14, 2005

The disappearing sidewalk

Stepping across to my favorite bookstore entails crossing this stretch of gravel. This place has the air of one where progress and construction are imminent. In truth, the gravel has been here for two years. The red bricks meant to cover it have appeared, disappeared, appeared, and recently disappeared once again. Some materials, to fill the gaps between the bricks, recently lay in white plastic sacks in a cluster outside one store. Those too are gone. Anything that is not nailed to the floor or high out of reach has been spirited away. But no one touches the gravel, though one day I believe they will discover its value for sound effects and will scoop it away. Then the road will be stolen, foot by foot, until there is no tar, and then the sand beneath will go too. Underground telecommunication pipes will be the new pavements, before they too are finally gone. Arms spread wide, we will balance precariously on them and dream of murder like Shalimar on a tightrope. Inch by inch, everything will disappear.

Four Septembers go by

Here's one account, by Sukhdev Sandhu, in the London Review of Books:

"A woman trips in the middle of the street and a dozen people all rush to help her. Strangers grasp each other by the wrist or the shoulders as they speak; they suddenly need to feel warmth, a human pulse ... And at every intersection clumps of people stand mesmerised as they gaze at the smoke fluming up in the distance. 'Where exactly was the building?' one asks. His friends aren't sure. Like many of the city's residents they've long taken the skyline for granted. Only tourists and newcomers ever look at it that closely."

Tuesday, September 13, 2005

55 words on 1st-grade love

Michael Higgins tagged me with the 55-word story thing, so it's all his fault. Take revenge by heading over to his rather interesting site: Chocolate and Gold Coins.

Cold turkey

And just two days ago Flintoff, Warne and Federer painted our tv screens red. Now there is Ganguly'x XI vs Mugabe's riff-raff. Bring those three back, even if it's only in replays.

Monday, September 12, 2005

Travels to unknown places

At airports, when there is time to kill, I sit beneath giant flipboards that announce where planes are headed and what their current status is. These black boards, with their green and red lights blinking, are magnets for the mind. The plane to Reykjavik is currently boarding at gate 12, and there is a last call at gate 3 for the Emirates to Johannesburg. Beneath it a family dressed for a safari scurry somewhere; a lady struts past, her intoxicating scent whipping those in her wake; everywhere, different nationalities and colours are rummaging and talking and heading in similar directions as they weave through the airport's processes.

Everybody is going somewhere. I am too, but I know what lies there. And so the journey loses some glitter. I know the roads and paths at the other end. The streets will be tarred, yellow dashes painted against their dark surface, there will be a traffic jam there, and it is advisable to leave a tip no less than 17.5% of the overall bill. This is what I will find there. But the other names on this board, they will take me to the Palace of Versailles where forgotten history lessons will come back, to Uluru where the stories haven't changed for a thousand years, to the Bosporus, to cave paintings at Lascaux, to the mosque in Cairo, to the world's great libraries, to the gun markets in Somalia, to where Rai comes from, to the Northern Lights, and to other places that are significant in personal symbolism if not history.

And the names keep flipping, and the signboard taunts, "This is where you could go and you could go there too, and that, my friend, is another flight missed, but wait, there is another in that direction boarding at the gate nine strides away. Go on, you know you want to." And I think, "just wait, it's a matter of time. One day you will run out of names, run out of places for me to visit. Your flips will be useless, every name visited and learnt from in this lifetime. Then you can taunt someone else enough for him to turn red, loosen his tie and say to you, 'That's it, where's my rucksack?'"

But it's just a signboard. What does it know how much it says with a single flip?

Saturday, September 10, 2005

Judging books by their cover

But design does not stop at the book jacket. How well the letters are spread out, how comfortably spaced the lines are, what typeface to use, how to signify the start of a new paragraph, how to design the title of each chapter; all these are dilemmas decent designers would mull over as one would a math problem or a swish of a paintbrush. Then there is the dilemma of generosity. How much can the designer give to the reader and the author without compromising his own beliefs and chances of an award? But this problem does not apply here. It is the first lot that are a concern at the moment.

Some publishers carpet-bomb us with words; Penguin in India is one of those culprits. One look at most of their books and you would imagine design was something those crazy foreigners with their subversive western influences did for a lark. After all, why spend time on how a book looks if people buy it for its content? That is an argument with no end. But I have empathy for the reader and the author. To be forced with a sea of words printed at an angle in blotchy ink on gritty pages is mildly unpleasant and bloody irritating. To see your manuscript mauled spectacularly and called a book only because it eventually has a fleeting resemblance to one can also be upsetting.

Inspiration cannot be a hurdle. Beside these books lie designs that transform books into even more of a collector's item. The Master and Margarita is one such, as is the sepia-tinted Simon Winchester's Calcutta and Murakami's and Coetzee's books by Vintage. These designs become the author's signature. Look at John Grisham. The Pelican Brief: crackled backround, beveled typeface. The Rainmaker: same. The Street Lawyer: more of the same. (Grisham is being used for the signature aspect, not the quality of design.)

The inspiration is all there. And surely publishers know how much influence good design exerts. How to describe the longing one feels on noticing a well-designed book, regardless of the subject? It is like noticing an interesting person from a distance and being convinced that compatibility is inevitable.

"There is nothing more fit to be looked at than the outside of a book," said Thomas Love Peacock, a 19th century satirist, as quoted in this piece about the history of book covers in the Guardian. A cover can be seductive if the right hands dress it, but this is not the case at the moment. For numerous designers, designing book covers is a way of latching on to immortality. Why not tap these designers who are fed up of designing leaflets and making the client's logo smaller?

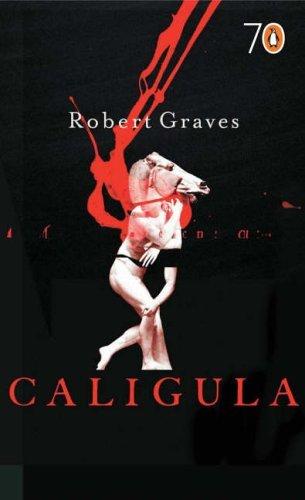

Now to the point. What initiated this post was Penguin's (the one abroad) boxed set of 70 pocketbooks. They are of remarkable design, each cover radically different from the last one. They not only appear to have not been created by the same hand, but they transcend nationality and eras. The different people credited behind each book is a reason for this: it ensures that the designer is free to concentrate on one design without worrying about a 'look' for the series. And yet they appear to be part of a set. One that made me laugh had a picture of a gruesome-looking breakfast which few would survive if they ventured toward in the first place: it was for George Orwell's In Defence of English Cooking. Zadie Smith's book was eye-catching too, as was Caligula.

There are possibilities all around, especially in a country as rich in chaos as this, where every day is a visual surprise. But unfortunately good design is not seen as an end in itself, and sometimes it is not seen at all. It needs more than skilled practicioners. It needs the people who matter to truly need it back.

Here is the Guardian essay again. It is worth a read. And below is the cover of the Caligula pocketbook, taken off Jai Arjun Singh's site.

Thursday, September 08, 2005

A clash of dreams

Yesterday James Blake stepped out of the US Open, a man defeated but proud, who plays sport as it should be played: with courage, tenacity, and a smile. A man who plays the sport to his own music, as champions do. One day a slam will be his. The parallels with English cricket are there. These are parallels that run with every sport and every sportsman. Tragedy, success, jubilation, despair; all ingredients of life and its reflection in sport.

England has seen hell. Beaten at one’s own game, the losses are doubly galling for a game’s masters are expected to not lose their grip. Now they have found themselves and taken us with them as they have made one realization after another, like an adolescent superhero slowly discovering what he is capable of. These realizations are perhaps nowhere else as dramatic as they are in fantasy and sport, which are close relations. The other superhero has discovered what old age can do and how quickly it sets in, and it is now left with the grit and sheer desire that are the residue of champions’ evaporated fantasies.

And when these five days pass, what will we feel? A sense of loss is inevitable for how many series have taught us more about how games can be played, about how so much that went before was wrong only because so much here has been right? Some of us will come out rejuvenated in what increasingly looks like a new era in this game. We are here now. Where will we be when this era ends?

In five days these Ashes will be over, forever recorded only on paper and film and memories that are inevitably exaggerated. All the noise, all the sound, all gone. These five days will be beautiful; they will be all about sport, all about life. Please don't let it rain.

Wednesday, September 07, 2005

God at ungodly times

So you go to the window and there they are, the scums. And there's a police van behind them, driving slowly, providing protection to this lot. Not arresting them, but making sure nothing happens to these...these innocents. Delightful place, this city.

Monday, September 05, 2005

The Hyderabadi angle

I wonder if Mirza then, like the other two, is a 'touch' player; a player whose game is based more on instinct and harmony. Like David Gower as well. Which is why, when they're out of sorts, they don't merely look terrible, they appear to have walked into the wrong sport.

Sunday, September 04, 2005

Sehwag's feet and Benaud's brain

Benaud's admirable trait is rare, though. As cricket writers - actually, I'll stick to myself for this example - as a cricket writer, there are so many voices out there expressing so many opinions that you need to say something different, radically different, to be heard. And so you say it. And then there are so many voices after yours that your opinion is often lost in the melee. What's infinitely tougher is to keep thoughts to myself.

The treacherous guest

Early today, he cleared his throat after a long silence, making branches shake and trees bend backward and sending stray dogs whimpering, scampering for a roof. He groaned a low but loud groan, ending with a loud rumble, like explosions on the horizon. He promised violence but we couldn't be fooled. What happened five weeks ago could not really happen so soon again, could it? And yet we watched the sky, just in case. It rained lightly, every now and then, sometimes heavy but never for long, and always silently. All the more reason to watch his type, especially after what happened in July. All nice and good at first, he could turn treacherous in a blink. Tragic, really. We had a good thing going, this irritating guest and I. Still, he remains comforting in some way.